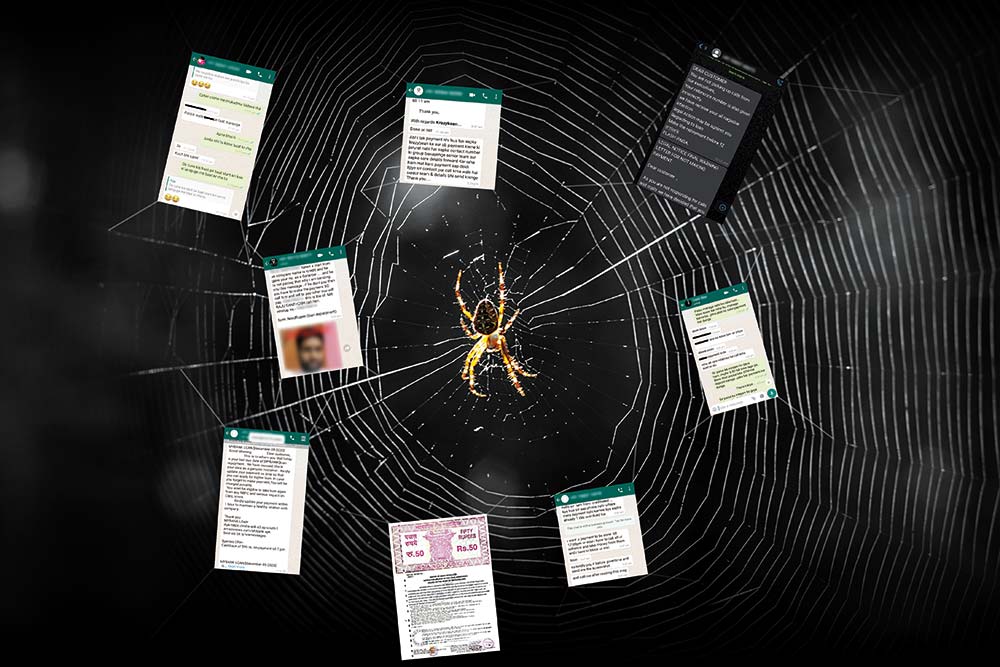

It’s a giant mobile-digital loan scandal. Like a tarantula’s, its web stretches outwards to Hong Kong, Singapore, Indonesia and China. In India, the reach is seen in several states such as Delhi, Maharashtra, Telangana, Haryana, Tamil Nadu, and Karnataka. Tens of thousands of borrowers are trapped in this net’s grip. Most were harassed, abused, and vilified, and some committed suicide. Hundreds of global and Indian companies, and thousands of thuggish recovery agents are involved in it.

Months after the scam was unearthed, the investigators were unable to put a figure on its size. In Telangana, contends Shikha Goel, Hyderabad’s Additional Commissioner of Police, Rs 25,000 crore was involved, which included repeated loan deals. The state police froze Rs 350 crore in 435 bank accounts. But this is only the tip of an iceberg. As the central enforcement directorate and states’ criminal investigation departments get into the act, the numbers can be five to 10 times higher.

The masterminds of the deathly rip-off are Chinese nationals, young globetrotters in their late twenties and early thirties, based in China and India. At present, five Chinese and 36 Indians are behind bars. The former include the brains behind the pains of the borrowers, and their families and friends. The 27-year-old Zhu Wei (Lambo), who was arrested at the Delhi International Airport, heads a few global companies that were involved in the fraudulent loans.

Blame it on COVID-19, which led to the loss of millions of jobs, salary cuts and delayed payments. Caught in a vicious cycle, many hungrily and desperately scrounged for help. Voila! There were hundreds of digital-mobile loan apps willing to extend money in a jiffy. A consultant in Telangana says that her first loan of Rs 2,500 was transferred in 10 minutes – “no hassles, no documentation, just a few clicks to send photographs of Aadhar and PAN, followed by a live selfie.”

At this stage, the typical human traits related to desperation, greed and unusual confidence kicked in. The money was easy to get, the interest rates were high at 20 to 50 per cent, calculated on a daily or weekly basis. Fascinated by the ease of getting money, many borrowed recklessly. They took small amounts, but from as many as 50 apps. The 24-year-old Kirni Monika, who consumed poison and died, got Rs 5,000 each from 55 of them. Her outstanding including interest shot up.

Others were careful; they borrowed and repaid on time, i.e. within six to seven days. But at some stage, they too got stuck, when they were unable to repay on time. Mumbai-based Prabhu Jeyabalan, 33, began his loan journey in March 2020, and easily paid back eight of them. However, in early December 2020, he was stuck with a Rs 20,000 loan that he needed urgently, but could not repay. A similar thing happened with the Telangana-based consultant, who was mentioned earlier.

The borrowers didn’t realise the three tricky parts of the loans. The first was that although the money was easy, the interest rates were so high that they quickly totted up to unmanageable proportions. K Santosh, 36, who committed suicide, found that the interest on his principal amount of Rs 51,000 was actually Rs 50,000. KV Sunil, 28, too killed himself when his loan of tens of thousands of rupees became a non-payable amount of Rs 2,00,000. The interest meter seemed unstoppable.

Second, many were caught in an initial-cozy, later-shattering debt cycle. As they repaid the loans several times within the stipulated six to 15 days, they felt comfortable. Little did they think that they would fail to do so for extraneous reasons! They were completely unprepared for such a situation. The third was the inevitable debt trap. Borrowers were asked to repay existing loans through fresh ones from other loan apps. This led to a never-ending and constricting web of loans.

However, the borrowers had no clue about the trauma they would face as defaulters. Threats, abuses, blackmail, and forged documents were used by the recovery agents of these loan apps. Outlook Money accessed screenshots of dozens of WhatsApp texts sent to the recipients. On the last repayment day, a borrower was told that “today is the last due date.” If she didn’t pay, she was informed: “you will be charged penalty,” and “you won’t be eligible to take a loan again from any Non-Banking Financial Corporation (NBFC).”

Defaulters received intimidating texts that they would be shamed in front of their families, colleagues and friends. When people downloaded the apps, they unwittingly gave permission to the lenders to access information stored on their mobiles. This included contact lists and other Internet activities like shopping and banking details. Borrowers got screenshots of their contact lists, along with coercive messages that the latter will know about their so-called misdeeds.

Jeyabalan’s office colleagues received emails that he was a defaulter and cheater, who hadn’t paid back his loans. One day, someone who claimed to be a director in the loan app company, called at 8 pm. He threatened to come to Jeyabalan’s house, and shame him publicly in front of his family and neighbours. It was then that Jeyabalan mustered the courage, and filed a complaint with the city’s police cyber cell. In some cases, the references to the loans were told that they would have to pay the money.

Forged documents such as legal notices, police complaints and unsavoury letters from Credit Information Bureau (India) Limited or CIBIL, which maintains every borrower’s credit score, were sent to those who delayed payments. The recovery agents regularly used abusive language in their texts. The Telangana-based consultant was asked to do whatever it took, even if she had to resort to the world’s basest profession, to return the money. There were texts sent to others, where abuse was common and repetitive.

Another victim, Rishi Meena, who took a loan, received what was dubbed as ‘Business Action Plan’. It listed five steps that the agents took to recover the loans. These were:

- All your relatives will be called. Dial history hack

- All relatives’ photographs will be sent to everyone

- All relatives will be added to one WhatsApp group

- The photos will be put on the social media site. You will appear in the newspaper, Instagram, Facebook (sic!)

- A police case will be filed against you. The file will be transferred to the district court

A senior police officer in Haryana details out the operations of the recovery agents, who had seven ‘bucket lists’ as their ammunition. On the first day of the default, bucket 1 and 2 would kick in, and include text messages and emails to remind that the payment was overdue, followed by threats and pressure calls. On the third day, the bucket 3 and 4 tactics implied screenshots of contact lists scribbled with a large ‘420’ or ‘fraud’, and personal details of the borrower.

Bucket 5 and 6 meant creation of a WhatsApp group that included the names from the recipient’s contact list, and constant reminders for repayment. The people on the contact list got several calls at odd hours. Bucket 7 was the last resort, as the borrower’s phone and email were flooded with forged documents and abuses. “This is the broad way the bucket system works. But the recovery agents had the discretion to choose the actual sequence of the ‘bucket lists’,” adds the officer.

Nothing was left to chance. If a person claimed that her bank’s server was down, the agents would promptly provide an alternative – pay through Paytm, RazorPay, or other payment gateways and e-wallets. If someone said that she didn’t have the money, the agents would immediately urge her to borrow the amount from another loan app, which was part of the same group. In many cases, the agents would not cut the voice calls unless the payments were made.

Everything was virtual. In fact, if an individual paid on time, there was no human intervention. The app was downloaded on the mobile, snapshots of Aadhar and PAN were sent through the phone, money was received directly into the recipient’s bank account, and was repaid into the apps’ accounts in banks, or through payment gateways and e-wallets. Only in the cases of non-payment did the human touch surface, but it too was through voice calls, WhatsApp texts, and emails.

The entire recovery operations worked without any face-to-face contact between the agents and the borrowers, and through dozens of call centres spread across the country. These were, in turn, owned and managed by, or linked to the loan apps. Hyderabad’s ACP Goel says that her department raided six call centres located in Gurgaon, Hyderabad, and Bangalore. The callers, 2,000 of them, contacted people across several states, and not just in Telangana.

According to the police sources, the recovery agents were young and educated. While most studied till the eighth standard, some were graduates. They were hired for regular call centres. They were, however, trained to use abusive language and shaming tactics to harass customers and get the money back. Each morning, they got a target sheet of the defaulters, along with their past performance scores or ability to return the money.

Based on police interrogations, it seemed the agents thought their role was similar to recovery agents working on behalf of established banks and NBFCs. They had little sense—possibly they were brainwashed—that their actions were illegal, or that they were party to a global loan scandal. They thought that any procedure used to get the money back was legitimate. After all, how can lending institutions survive, if most people default?

None of them knew that they were an integral part of an enormous swindle, which had perfected the art of preying on the financial weaknesses of COVID-afflicted people. They were getting people addicted to easy debt, extracting high interests from the borrowers, and then shaming them—forcing a few to commit suicides—in case of defaults. Like a web, the empire—loan apps, payment entities, and call centres—was interconnected in several ways, both legitimately and illicitly.

To begin with, there were hundreds of loan apps that vied to trap hapless customers. So, far, the police have counted 197 such apps, and many were banned by Google. They were linked to the call centres and operated through hundreds of bank accounts, as well as accounts on Paytm, RazorPay, and other options. The top guns involved were Chinese, based in countries like China, India, and Singapore. Some of their pasts are quite colourful.

Liang Tian Tian is a Chinese woman, who married an Indian Parshuram Lahu Takwe, and the couple ran a call centre in Pune. The call centre worked for several firms such as Ajaya Solutions, Bienance Information Technology, Epoch Gocredit Solutions Private Limited and Truthigh Fintech. Another operator, He Jian, alias Mark, came to India in July 2019 on a business visa and joined as a representative on behalf of the Chinese nationals, Xu Nan Xu Xincang and Zhao Qiao, who are directors of the loan app companies.

As can be seen from the names, most of the fraudulent companies were either operating in tech or fintech. Hence, it is critical to examine where they got the initial capital to lend. One of the easiest sources was to borrow at a lower interest from the NBFCs, and lend it to individuals at higher rates. Another funding source, contends Save Them India Foundation that was formed to help the loan victims, was crypto-currency, like Bitcoin, which was possibly earned through illegal means.

Lambo, one of the arrested Chinese whose name was mentioned earlier, ran an investment apps scam, which was like ponzi schemes, and offered huge returns to the investors. This money was used for loans, which earned huge interest. Funds came from Hong Kong and Singapore. More importantly, the initial capital and profits were circulated at a fast pace—loans were only for a few days—to generate volumes. In many cases, the loans disbursed and paid back were five to 10 times higher than the original amount.

Police probes found that it was tough to either pinpoint the funds’ sources or destinations. ACP Goel explains, “We are working on the money trail. Initial investigations reveal that funds from NBFCs or apps were credited into bank accounts, and sent through payment gateways to the borrowers. On their return, repayments of loans, they followed different trails. Instead of going back to the NBFCs or apps, the money went to different merchant IDs and accounts.”

The problem, as we stated earlier, is that everything is connected. Take the case of four firms—Liufang Technologies, Hotful Technologies, Nabloom Technologies and Mashangfa Technologies. The first three were incorporated on January 9, 2020, and the last one on February 14, 2020. The four firms had two common directors, Palle Jeevana Jyothi and Selva Raj Singi, who were appointed on September 8, 2020. Their initial authorised capital was the same, Rs 10,00,000 each.

Manjunath Nuthan Ram and Chinnabba Rajasekhar, who were directors in Mashangfa Technologies, held the same posts in 14 other companies. These additional firms were incorporated between February and August 2020. As we have seen earlier, there were common Chinese links between the global and Indian loan app firms, as well as the various call centres located in the country. Police say that even hundreds of bank accounts were operated by multiple entities.

Most of these tech and fintech lenders were not registered with the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) to provide loans. However, they managed to use renowned players like Google Play and Apple App Store for the individual downloads of their apps. Also, the fraudsters created accounts on recognised payment gateways. If a potential customer searched for an app, she was bombarded with ads from the others. Everything seemed above-board. Such aspects convinced people that the loan apps were possibly genuine.

Only now, after a dozen suicides across several states, and harassment of thousands of borrowers, have the regulators, industry players, and investigators woken up from their slumber. The RBI set up a committee to define and design rules for loan apps. Google said that it has barred the erring apps, told app developers to tell the others to follow the laws of the land, was likely to ban those who didn’t adhere to them in the future, and help the investigations. The industry clamoured to weed out the erring lenders.

But who will claim the debris of debt, and bodies of the dead?

jyotika@outlookindia.com