For years, the warnings came in whispers, people losing their salaries to “easy win” app-based real money games (RMGs), families quietly pawning assets to chase back lost money, and late-night calls to helplines after one click too many.

Is Real Money Gaming Ban The Endgame?

Real money games didn’t just ruin several lives financially but also had a deep psychological impact on the gamers, which the recent online gaming ban stopped in its tracks, but there are others who rue the ban, warning of job losses and the rise of black market apps. What’s the endgame?

The government finally decided it could no longer treat these stories as isolated tragedies, and on August 22, Parliament passed The Promotion and Regulation of Online Gaming Act, 2025, a law that drew a sharp line for India’s online gaming sector.

Policymakers say the legislation to ban RMGs is designed to curb addiction, financial ruin and social distress caused by RMG platforms that thrive on misleading promises of creating quick wealth, with the middle class and young adults being the most exposed.

Union Minister for Electronics and Information Technology Ashwini Vaishnaw noted in Rajya Sabha in August that according to an estimate, 450 million people have been negatively affected by online money games and faced a loss of more than Rs 20,000 crore, according to a Press Information Bureau release.

The ban has finally rid several gamers, who lost lakhs of rupees in RMGs, of an addiction that was ruining lives, financially and mentally. At the same time, it has also hit hard game developers, employees working in these companies who suddenly find themselves jobless, as well as skilled gamers who claim to have understood the play.

Let’s find out what the ban is about, how it has benefitted players who were addicted to it, and what makes the law controversial.

The Ban

The new law is a national, non-bailable, and centrally-enforced law. It has done something simple, but decisive. It has demarcated online games into three categories to draw the line between what lawmakers saw as addictive money traps and what can be considered healthy digital play.

Online Money Games (OMGs): Any game, skill or chance, where users pay fees or deposits with the hope of winning back money or equivalent rewards have been banned outright. Rummy, poker, fantasy sports; if there’s cash on the line, it is now banned.

E-sports: Competitive, skill-based digital tournaments, have been officially recognised like other sports. With no bets or wagers, these are to be promoted and nurtured as a sporting ecosystem.

Social Games: Games meant for fun, learning, or recreation, those with one-time access fees or subscriptions, but no staking of money would be regulated, but do not fall under the ambit of the ban.

Penalties: Offering an online money game could invite up to three years in jail or fines up to Rs 1 crore or both. Repeat offenders would face up to five years in jail. Even financial institutions and payment gateways are now barred from processing these transactions, effectively cutting off the oxygen supply to these platforms. Advertising money games is a punishable offence, too, with up to two years in prison or a fine up to Rs 50 lakh for the first strike or both.

To police all this, a new authority is being set up, the National Online Gaming Commission (NOGC), tasked with licensing, categorisation, and enforcement of the Act. It also stipulates setting up Online Gaming Appellate Tribunal for disputes.

At present, many gaming companies and industry bodies have filed petitions challenging the Act, setting the law up for a major legal battle ahead. The Supreme Court consolidated all the petitions filed by gaming companies. On October 7, 2025, the petitioners sought interim relief from the apex court, arguing that the law had shut down their businesses completely, forcing layoffs across the industry. The next hearing did not take place before the article went to press.

Deepanshu (name changed), a 33-year-old from Maharashtra, remembers the early rush of his foray into online RMG. In 2017, he downloaded a rummy app, convinced his skill at playing cards could translate into real winnings. The first few games seemed to prove him right. “I pocketed Rs 5,000 here, Rs 10,000 there, I thought it’s easy money,” he says.

But the streak did not last long. Soon, every small win was followed by a sharper loss—Rs 2,000 gone in just 15 minutes, another Rs 3,000 the following week. Each loss pushed him into putting more money to recover what he had lost, something he now describes as a “domino effect”. It was only when the losses piled up to Rs 30,000-40,000 that he realised he was caught in a vicious cycle.

But the platforms didn’t make getting out of the trap easy. He says: “Relationship managers offered bonuses: deposit Rs 10,000, get another Rs 10,000 free.” For a while, he bought into the illusion. Eventually, he stopped, but not before it caused a substantial financial and mental burden.

The Promotion and Regulation of Online Gaming Act, 2025 is a national, non-bailable law that has banned any online game that promises monetary reward

If Deepanshu’s losses were measured in thousands, Shrivastava (name changed), a 50-year-old from Andhra Pradesh, counts his in lakhs. For nearly a decade he played rummy online, chasing the thrill that money brought to a game he once enjoyed casually. At first, he played occasionally, but soon it became a daily activity. “I lost Rs 2-3 lakh in just one year,” he says quietly.

The financial strain was only part of the problem. Shrivastava speaks of sleepless nights filled with anxiety and an itch to recover his losses by putting in more. Calls came from the platforms if he logged off for too long. “It became an addiction and affected my health and sleep,” he says.

It was the government-enforced shutdown of RMGs that finally broke the cycle for both Deepanshu and Shrivastava. Without the apps on his phone, Shrivastava’s constant urge to play has eased. For him, the ban isn’t just regulation, it’s relief.

The Insider Story

Hardeep (name changed), who once worked as a retention manager at a mid-tier online gaming company, rips the curtain down on how the industry designs traps to keep gullible gamers hooked. Players may believe they are making choices, but Hardeep reveals how those choices were engineered to a great extent.

His job was simple: keep players coming back by talking to them and encouraging them, dangling cash and rewards or using bots, and ensure they don’t make too much.

At the top of the food chain were the so-called VIP players, who deposited Rs 1-2 lakh every month. They were called “whales” and entire teams existed only to keep them engaged, he says.

Hardeep recalls: “Every morning we had to call them, greet them, talk strategy like we were their coaches. But we weren’t experts. Sometimes, we were like call centre staff with one brief: don’t let them stop playing.

And if the whales hesitated, bonuses were dangled: deposit Rs 10,000, get an extra Rs 5,000 or more to play. In one case, the gaming company he worked for even gave a loan of up to Rs 70 lakh to a player who had burnt through his savings. The loans were intended to drag the player back into the cycle and bots were routinely used to simulate real players.

At first, the bots were made to lose so that newcomers felt confident. Later, their difficulty could be ramped up, ensuring players almost always lost.”

The consequences were devastating for some gamers. He talks about seeing suicide notes from distressed players. One involved a government schoolteacher who sold his land to keep playing, only to end up penniless. In another case, a young man on a Rs 50,000 salary, spent every rupee on gaming, and kept borrowing from friends to keep going.

Hardeep says: “They spoon-feed you with bonuses, with cakes on birthdays, with fake friendship. It looks like care, but it’s not. Their only agenda is to make you play.”

Unethical practices didn’t define all the platforms though. Says Jay Sayta, a technology and gaming lawyer based in Mumbai, “There may be certain renegade operators who may not have followed responsible gaming practices, code of conduct and ethical marketing practices, but most of the online skill-based RMG companies in India strictly did not allow bots on their platform, and followed responsible and ethical marketing practices.”

The Psychology Of Play

Dr. Prerna Kohli, a clinical psychologist and founder MindTribe.in, explains why stories like theirs follow such a familiar arc.

The hook often begins with a small win, like in the case of Deepanshu. “A small win feels like luck and a small loss like a challenge. That’s how the trap is set,” she says.

From there, players enter the cycle of chasing losses. Srivastava admitted he played more after losing lakhs, trying to recover his losses. Psychologists see this often: the human brain struggles to accept a loss, so it reinterprets it as a temporary setback to be fixed with “just one more round”.

The structure of the games intensifies this. Says Kohli: “These apps are not neutral. They are designed with nudges—push alerts, daily bonuses, near-miss effects—that keep people engaged. The environment is engineered to maximise time and money spent.”

Each hand, spin, or match produces an immediate outcome. Win or lose, the result lands instantly, firing the brain’s dopamine circuits. Add in near-misses, when a card, number, or player choice almost pays off, and the illusion of control grows.

“Players believe their choices matter—picking the right card, choosing the right captain, spotting a pattern. But the system is tilted. Near-wins trick the mind into thinking that skill played a role. It’s a false sense of control, but it feels real in the heat of the moment,” Kohli explains.

Add in bonuses and personal calls, and players start believing they have control. Kohli adds: “A casino used to mean travel, time, maybe even dressing up. Now it’s just a tap on your phone at midnight in bed. No effort, no pause. And the brain gets hooked on to those fast, unpredictable wins, near-misses too.”

The games are designed in a way where every win or loss fires the brain’s dopamine circuits, urging replay. Difficulties are ramped up as the game progresses

Over time, the psychological toll extends far beyond the game screen. Anxiety builds, guilt creeps in, and sleep gets disrupted as gaming stretches into late nights. Families feel the brunt—arguments over money, emotional distance, broken trust become all too common.

Split Screen Reaction

While the government maintains the Act was framed to curb addiction, financial ruin, and social distress caused by “predatory gaming platforms”, not everyone sees the sweeping ban as a reform. Many seasoned players and industry veterans argue that by banning skill-based fantasy sports with chance-driven apps, the government has lumped everything into one bucket.

Sameer Kochhar, chairman of SKOCH Group, a thinktank and full services consulting firm, calls it “a prohibitionist shortcut that may backfire”. “If the logic is solving addictive behaviour, then why cherry-pick gaming? Addiction exists in online astrology, futures and options (F&O) trading, and even OTT binge-watching,” he says.

Sayta adds that the new law goes against the federal structure of the Constitution, as health, sports, entertainment, amusements, gambling and betting are all state subjects, and states have exclusive legislative competence on regulating online games and gambling/betting activities. “Besides, the new law does not differentiate between games of skill and chance, prohibiting all kinds of online money games, thereby going against decades of established jurisprudence and several Supreme Court judgments.”

A three-year study by SKOCH, released in October 2025, has proposed a ‘Risk-Purpose Matrix’, classifying games into green, yellow, orange, and red zones, based on purpose and harm potential. Under that model, only the highest-risk ‘red-zone’ games would face prohibition; the rest would be licensed with safeguards, such as spending limits, transparency dashboards, and parental controls.

‘Skilled’ Gamers Hit: For players who had spent years treating it like a profession, or even just a disciplined side income, the sudden full stop felt more like a crash. Abhigyan’s (name changed) story opens a different playbook than Deepanshu’s and Shrivastava’s. Where the latter saw loss, Abhigyan saw strategy; where others felt trapped, he felt in control.

Abhigyan, who began playing fantasy sports in 2017, insists it’s neither about pure luck nor pure skill. “Maybe 7-9 per cent is skill,” he says. But that sliver of skill, reading pitch reports, tracking player stats, learning how contests work, were enough for him to build a system within Dream11, a fantasy sport. He favoured smaller, head-to-head contests instead of giant pools. He tracked every rupee, invested consistently, and pulled back when the odds weren’t in his favour. The result? A Rs 9 lakh single-game win at his peak, and an average profit of around Rs 3 lakh a month.

Yet, even he concedes the field tilted over time. The gap between seasoned players and newcomers widened and pro players like him gained access to Dream11’s inner circle: free match tickets, player meet-and-greets, even invites to headquarters to suggest features. “Beginners, meanwhile, often played blind, relying on ‘guru’ advice while bleeding small, but steady amounts, and the system became less fair,” he says, though he doesn’t believe bots or outright cheating were at play.

Some players say a blanket ban will drive legitimate operators underground and lead to the mushrooming of grey-market apps and VPN-based play

For Yatharth (name changed), a corporate lawyer and early Dream11 adopter, the skill element was even sharper. During the Covid pandemic, fantasy sports became a side income for him.

“People call it satta, but I saw it like the stock market, where without research, you’ll lose,” he says.

The Dream11 team refused to comment on our queries regarding RMG practices and the impact of the new Act on players and the play.

What frustrates Yatharth most is how the law drew no distinction. He says: “High courts and even the Supreme Court had earlier classified fantasy sports as a ‘game of skill’. Yet the 2025 Act lumped it together with Rummy and Poker under money games.”

For Shivam (name changed), another fantasy sport player, the impact was even more direct. He wasn’t just a player; he had turned Dream11 into a career.

He first joined in 2015, casually. But when baseball was introduced during the pandemic, his fortunes changed. He won big in Grand Leagues, topped Dream11’s MLB leaderboard, and soon caught the company’s eye. By 2022, he was working as a marketing influencer, first on short contracts, then during marquee tournaments like the IPL and World Cups. This year, he finally had a steady monthly income from Dream11 promotions.

Then came the ban. Overnight, the app that had once given him recognition and livelihood was gone. “For me, the ban wasn’t about losing a game. It was about losing stability,” he says. For Shivam, it ended a career just as it was taking off.

Rise Of Grey Market Apps: Kochhar warns that a blanket ban only drives legitimate operators underground. “After prohibition, you have no one to catch,” he says, citing the rise of grey-market apps and VPN-based offshore play. “You’re taking away the citizen’s recourse to justice; the problem doesn’t vanish, it just hides away.”

Sayta agrees: “We are already seeing illegal offshore betting operators aggressively offering their services to Indian customers. This is only expected to continue and grow as it is impossible to track and enforce prohibition on thousands of offshore gambling websites which keep on changing their domain and brand names on a daily basis.”

Says Sayta: “The Supreme Court will decide on the Constitutional validity of the new legislation. Instead of a complete ban, the government could have looked at alternative measures, such as appointing a regulatory body to oversee and impose strict deposit, time and age limits and restrictions on advertisements.”

The Endgame

Financial advisors draw parallels between online gaming, betting and gambling, which lure users with “easy money” and a “side income”.

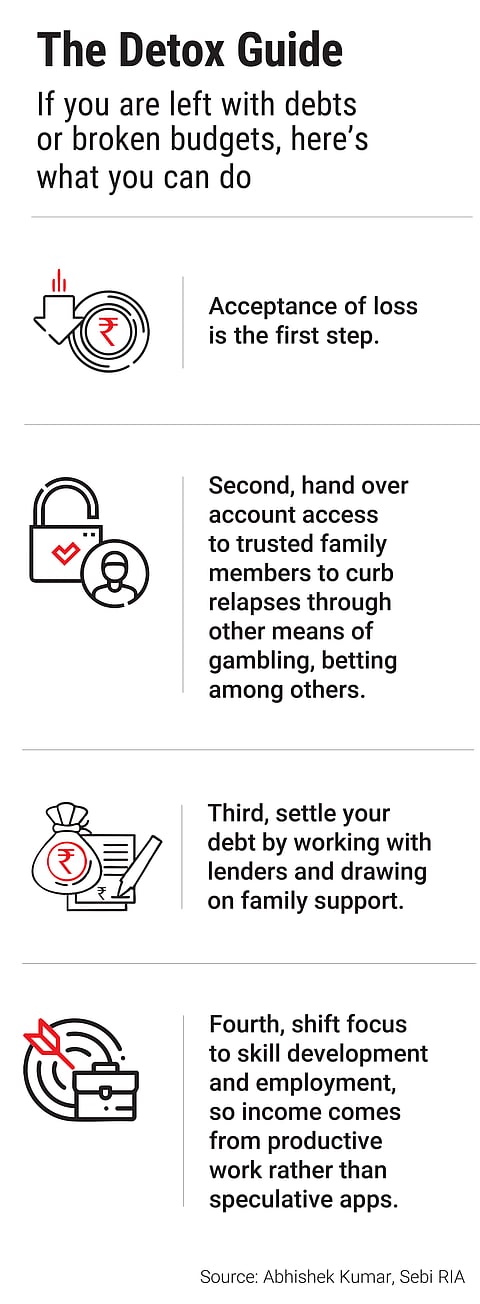

Abhishek Kumar, a Securities and Exchange Board of India-registered investment advisor (Sebi RIA) and founder of SahajMoney, a financial advisory firm, says many players make the mistake of treating fantasy sports or RMGs as “side income” or “investment”, but that’s not correct.

He explains: “These games act as psychological traps that mirror gambling addiction patterns, and considering them as investment or side income is a mistake. Odds are stacked against the players as the house always wins, whereas only a few make money from it.”

The result: households running into stress. Emergency savings depleted. Loans taken to cover gaming losses. Even essentials like children’s education and healthcare are sometimes compromised.

Some skilled gamers draw parallels with stock market investing, but that’s erroneous too. The parallels can only be drawn with short-term trading and the urge to make quick money, but not with long-term investing that can help achieve your financial goals. A report by Sebi released in July 2025 showed that 91 per cent of individual traders (about 7.30 million traders) in the equity F&O segment incurred losses in FY25. The trend was similar to that observed for FY24 by Sebi.

Kumar says: “Although both involve risk-taking with money, but RMG and stock markets are fundamentally different. Usually, over a long period of time, the returns from stock markets have been positive and leads to genuine wealth creation due to value creation by underlying stocks for their shareholders. In contrast, RMGs represent pure consumption with no underlying value creation.”

However, the crux of the matter lies in fighting psychological demons like addiction and greed that lead people into activities like betting and gambling, which promise quick money, but at a humongous amount of risk. Online gaming falls into that domain.

Bans, Kohli believes, provide some relief, especially for those already trapped. “A ban slows things down, but bans alone are not enough. Addiction requires active treatment: counselling, support systems, even financial guardrails like payment caps.”

Many online and seemingly harmless games can be a drain on players’ money because they encourage in-game purchases, which can be addictive. The idea is to replace the thrill of online gaming with something more constructive.

Kohli explains that the thrill people feel while gaming isn’t really about the game itself, but about the dopamine rush that comes from risk, reward, and competition. “When we remove the game, that chemical craving for stimulation remains. The key is not to suppress it, but to redirect it.”

She says constructive replacements include activities that give a similar sense of achievement and excitement. “Things like fitness challenges, learning a new skill, volunteering, or even gamified financial apps that reward saving rather than spending can help. Social connection also helps; joining communities where progress is celebrated can satisfy the same emotional need that gaming fulfils.”

Making money is tough and making your money work is tougher. Shortcuts like online gaming, betting, gambling and even short-term market trading are more likely to land you in trouble than make quick money for you.

anuradha.mishra@outlookindia.com