In India’s bustling metros, where ambition thrives and millions arrive with dreams of better lives, there is a crisis unfolding that is hard to miss—a dearth of houses these migrant employees (low- and mid-income) can afford to buy. The crux of the problem lies in the question: how much does an affordable house cost and how big or small is it? The government and different private developers have different definitions, and with the rising cost of real estate, what was once affordable may no longer be so for a large section of the population. The recent rate cuts by the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) may make a difference in terms of the equated monthly instalments (EMIs), but that will have no bearing on the original cost of a house.

Affordable Housing Crisis: Middle Class Left In The Lurch

Once heralded as a vehicle for inclusive growth and national development, affordable housing now finds itself squeezed between vanishing supply, stagnant policy response, and rising urban aspirations

In the past, a low-cost home on the city fringes or tucked into a newly developing area used to be the gateway for a modest-income family into urban homeownership. But today, that gateway is narrowing, and in some cities, it’s closing entirely. Our research shows that the affordable housing segment, once the bedrock of India’s urban housing policy and a launchpad for middle-class house ownership, is gradually making a quiet exit. Developers are retreating from the segment, homebuyers are priced out, and the dream of owning a modest home, especially for low- and mid-income Indians, is fast becoming a casualty of the real estate market forces.

What Are Affordable Homes?

The government has a defined benchmark for affordable homes. Under the Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojana (PMAY-Urban), the classification is based on income slabs and carpet area. It defines affordable homes as houses having a carpet area up to 60 square metres (sq.m) in metros and 90 sq.m in non-metros valued up to Rs 45 lakh. Anarock Property Consultants defines affordable homes as those priced under Rs 40 lakh.

But finding a house with that pricing is nearly impossible in any tier-I Indian city today, especially where private developers are involved. Housing prices in most urban centres have moved well beyond this affordability ceiling.

Another key question for any buyer is: What exactly am I paying for, and how much of the space is usable?

On paper, the PMAY-Urban scheme lays out clear thresholds. For the economically weaker section (EWS), the carpet area should be around 30 sq.m (approximately 323 sq.ft), with a ticket size capped at Rs 35 lakh. For low income group (LIG) homes, the cap is 60 sq.m (646 sq.ft) at Rs 45 lakh.

But in most urban centres, especially the top nine cities, the proposals are theoretical because there’s hardly any supply in that category. A buyer in Mumbai, Bengaluru, or Delhi National Capital Region (Delhi NCR) scouting for a home is unlikely to find one in the Rs 40 lakh range. If they push the budget to something between Rs 50 lakh and Rs 1 crore, they might find one, probably on the outskirts which will involve a long commute time.

Besides, you may not get the space you are promised. That’s because of something called loading, which is the difference between the actual usable carpet area and the total super built-up area that buyers are billed for (see Carpet Area vs Super Built-Up Area, page 82). According to an Anarock report, in 2025, the average loading has reached 40 per cent across India’s top cities, a steep rise from 31 per cent in 2019. That means a buyer who thinks they are purchasing 1,000 sq.ft is actually getting just about 600 sq.ft of liveable space. In case of EWS categories, the space can become really crunched.

Prashant Thakur, regional director at Anarock, says this trend is a direct response to rising consumer expectations. “Buyers now want everything—gardens, gyms, lounges, but may not realise that they are paying for all that space as part of their apartment cost. There’s no cap on loading in most states, and builders aren’t obligated to reveal how much of a buyer’s money goes into actual usable space.”

So if a Rs 50 lakh-plus home is marketed as “affordable” in the real estate market, what is often unsaid is how much of that price is for elevators, lobbies, or clubhouses, and how little is for actual bedrooms and living space. The price per sq.ft might look attractive on paper, but the effective price per liveable sq.ft can rival that of mid-income or even a premium housing unit in some cities.

Affordability Redefined

Clearly, there’s a mismatch between what affordable housing entails and what’s actually on offer.

A recent report from PropEquity, a real estate data analytics platform, underscores the mismatch. The weighted average launch price across India’s top nine cities has risen to Rs 13,197 per sq.ft in FY25, a 9 per cent increase over the previous year. This means that even a compact 600 sq.ft flat now averages Rs 79 lakh, far above the Rs 45 lakh policy cap for affordability. In fact, the average launch price in Mumbai is Rs 34,026 per sq.ft, which makes it virtually impossible to deliver any unit under Rs 1 crore without heavy government subsidies or severe compromises on location and quality. This, despite the fact that weighted average prices seem to have risen in FY25 compared to FY24, according to the report.

The fastest growth in price hikes year-on-year (y-o-y) were seen in Kolkata (29 per cent-plus), Thane (17 per cent-plus), Bengaluru (15 per cent-plus) and Pune (10 per cent-plus) (see Rising Prices, Shrinking Affordability).

Even in the traditionally more affordable cities, such as Chennai (Rs 7,989 per sq.ft) and Kolkata (Rs 8,009 per sq.ft), homes priced under Rs 45 lakh are getting pushed beyond the city fringes with limited infrastructure, far away from the economic hubs.

What this data also highlights is what’s affordable in one city may not be so in another, given that the minimum threshold is higher in some. Says Samir Jasuja, founder and CEO of PropEquity: “Government’s affordable housing definition is not real. In today’s market, even Rs 50 lakh to Rs 1 crore can be considered affordable depending on the city. What is affordable in Thane is not affordable in Gurgaon.”

The Villains Of The Piece

Falling Supply: Jasuja points to an alarming contraction in the supply of homes priced below Rs 1 crore. He attributes this sharp shift to a decade of stagnant growth followed by a three-time price surge after 2020, fuelled by infrastructure-led growth, higher incomes, and rising land and construction costs. “Prices didn’t move from 2010 to 2020. But in just the last five years, that suppressed appreciation exploded. A flat that was Rs 50 lakh in 2020 is Rs 1 crore today, even in tier-II cities,” he says.

In a report published in April 2025, Anuj Puri, chairman of Anarock Group, said: “Affordable housing faced the sharpest pandemic fallout, with sales and new launches shrinking in the top seven cities. Our data shows that affordable housing sales share plummeted from 38 per cent in 2019 to 18 per cent in 2024, while the supply share dropped from 40 per cent to 16 per cent in the same period. However, a 19 per cent dip in unsold stock hints at sustained demand led by end-users.”

Location Premium: Plus, real estate prices can double within a 10-km radius, depending on the location. With the pricing of real estate becoming more localised and volatile, one-size-fits-all affordability benchmarks no longer hold. In cities with tight floor space indices (FSIs) and limited land supply, building compact, sub-Rs 45 lakh units is becoming commercially unviable.

Shift To Luxury: The price increase is also driven by rising input costs (land, materials, labour) and the developers’ tilt towards the premium segments, where margins are higher.

Jasuja says that profit margins in the affordable segment are wafer-thin, and developers are naturally gravitating toward the luxury segments, where returns are higher and investor interest is stronger.

“There is no demand problem. There’s a big shortage in supply in tier-I cities. Developers cannot deliver at affordable price points and prefer the premium market where margins are higher,” he says.

The Great Divide

Real estate in India is splitting into a dual economy. On one side, there’s a robust demand for lifestyle housing, luxury towers, and gated societies. On the other, there’s an abandonment of the entry-level buyer.

A recent home buyer report by Knight Frank India, titled Beyond Bricks: The Pulse of Home Buying, revealed that demography-wise, the homeownership purchase sentiment was pushed most robustly by high earners with annual incomes above Rs 50 lakh (91 per cent) and millennials (82 per cent) due to their higher disposable wealth and better financial security. Respondents from Gen Z (71 per cent) and lower-income groups earning less than Rs 10 lakh annually (72 per cent) had relatively lower homeownership sentiment due to affordability constraints, lifestyle flexibility, and early career mobility.

This is also evident in the inventory data. According to Anarock’s Q1 2025 Residential Market Viewpoint, new launches in the premium to ultra-luxury bracket (Rs 80 lakh to over Rs 2.5 crore) dominated the landscape, comprising 70 per cent of all new supply.

In contrast, affordable housing (below Rs 40 lakh) made up just 12 per cent, holding flat quarter-on-quarter (q-o-q), and mid-income housing (Rs 40-80 lakh) declined by 12 per cent.

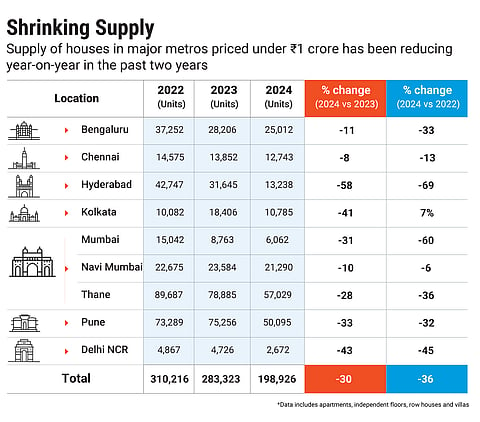

There’s more. According to PropEquity, available homes priced below Rs 1 crore shrank 36 per cent between 2022 and 2024, from 310,000 units to under 200,000 units. Some cities were hit harder than others. Hyderabad saw a 69 per cent drop in supply, Mumbai 60 per cent, and Delhi-NCR 45 per cent. Even cities like Pune and Bengaluru, once reliable destinations for affordable housing, witnessed 32 per cent and 33 per cent declines, respectively.

The latest quarterly data (January to April 2025) by PropEquity paints an equally sobering picture. The below-Rs 1 crore housing supply in India’s key markets fell by 38 per cent y-o-y, from 60,765 units in Q1 2024 to just 37,653 units in Q1 2025. Some cities have been hit harder than others. Hyderabad saw a 73 per cent drop, Kolkata 67 per cent, and Mumbai halved its already meagre supply in this bracket. Even in more resilient markets like Pune and Thane, supply dropped by 47 per cent and 34 per cent, respectively.

The only bright spots in this supply matrix are Chennai (+29 per cent), Faridabad (+82 per cent), and Greater Noida (+24 per cent), indicating developers are still testing affordable offerings in smaller or emerging areas. But they remain outliers in an otherwise shrinking market.

Meanwhile, luxury housing is not just surviving, it’s booming, show various reports. According to a Knight Frank’s Real Estate January-March 2025 report, sales of homes priced above Rs 2 crore rose 28 per cent y-o-y in Q1 2025.

For instance, analysis of the property registrations and demand trends data from Anarock over January-May 2025 in Mumbai shows that the average ticket price of homes was Rs 1.59 crore, the highest since 2019. In the corresponding period in 2021, the average ticket price was Rs 1.02 crore. This shows that in 2025, the market continues to record more sales of high-ticket price homes in comparison to more affordable ones.

These homes, many of which are upwards of 200-250 sq.m in size typically come with pools, gyms, landscaped gardens, and concierge services. The average ticket size for such homes in top tier-gated developments in cities like Gurugram, Mumbai, and Hyderabad has crossed the Rs 3.5 crore mark.

Says Niranjan Hiranandani, founder and chairman, Hiranandani Group, and chairman of the National Real Estate Development Council (Naredco): “Unlike some countries where the government provides housing as a form of social security post-retirement, in India, owning a home is intrinsic to long-term financial security. The decline in supply of sub-Rs 50 lakh homes, as highlighted by market data, is concerning, especially as this segment constitutes the broadest spectrum of housing demand.”

Government Initiatives: Too Little, Too Late

Since the pricing of houses offered by private developers is inhibiting, the next best option for low-income group is to look at government housing schemes under the Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojana (PMAY), but in the past the experience has not been smooth for most.

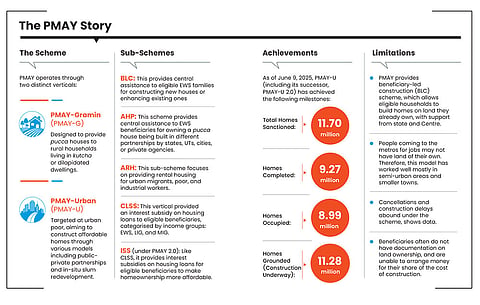

When the Narendra Modi government announced the launch of PMAY in 2015, the mission was to ensure “Housing for All” by 2022.

The scale of housing provision under the scheme has been unprecedented (see The PMAY Story). The bulk of this activity happened under the beneficiary-led construction (BLC) sub-scheme, where eligible households build homes on land they already own, with financial support from the state and Centre. Other sub-schemes under PMAY are Affordable Housing in Partnership (AHP), Affordable Rental Housing (ARH), and Credit-Linked Subsidy Scheme (CLSS), which has now been replaced under PMAY 2.0 by Interest Subsidy Scheme (ISS).

BLC: According to a study released in August 2024 on PMAY by the Centre for Social and Economic Progress (CSEP), a policy research organisation, BLC’s scale and coverage, especially in small cities where households have greater land ownership, has been impressive and has been a key driver of the overall programme.

The study assessed the physical progress of each of the four schemes, including BLC, AHP, ARH and CLSS sub-schemes in terms of completions, delays, and the houses that were not completed till the revised deadline of December 2024.

However, there have been issues with BLC as well. CSEP estimates compiled from various official sources indicate that 22 per cent of sanctioned BLC houses were cancelled; of the rest, 29 per cent were delayed (as of May 2023), which means they were not completed within the stipulated post-sanction period (18 months), as per the Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs guidelines. The key roadblocks behind these cancellations and delays were: (a) beneficiaries needed to provide documentation on land ownership, which some found challenging, and (b) they found it challenging to arrange their share of the cost of construction.

Moreover, while this model has worked well in semi-urban and smaller towns, it has done little to solve the affordability crisis in large metros, where the poor often don’t own land and live in informal settlements or rental accommodations.

AHP: Within the government’s housing framework, the AHP vertical was meant to fix the supply-side failure. Launched as part of PMAY-Urban, this model encourages states to partner with private developers or public agencies to build group housing projects, of which at least 25 per cent of the homes are earmarked for EWS beneficiaries (under 45 sq.m carpet area).

The central subsidy under AHP is Rs 1.5 lakh per EWS house, with states expected to add their own share. Yet, according to a CSEP study, for these flats to be financially viable, even on free land, the total subsidy needed is in the range of Rs 9-16 lakh per unit. The actual assistance falls short.

For developers, the profit margins are slim, and without adequate subsidy, the economics simply does not work. According to CSEP’s analysis, nearly 48 per cent of all sanctioned AHP flats were cancelled, and 43 per cent were delayed. Only 29 per cent of the completed flats were actually occupied by 2023.

Then there are land-related challenges, such as unclear titles, encroachments and regulatory bottlenecks, which have derailed numerous AHP projects. These issues lead to long delays between approval and construction, compounding costs and making projects unviable.

Says Hiranandani, “AHP often struggles with financial viability for developers due to lack of incentivisation, high costs related with approvals, development premiums, and taxation challenges such as the absence of Goods and Services (GST) input tax credit, which disproportionately burden developers’ balance sheets.”

Jasuja agrees: “Developers are not drawn to AHP or affordable housing schemes simply because the profit margins are far thinner than in luxury projects. And once a project is launched, costs can go up over the 3-4-year construction window. Without a meaningful incentive structure, affordable housing remains low priority.”

He adds that well-meaning initiatives, such as Haryana’s Deen Dayal Awas Yojana, which capped sale prices while subsidising land, were gamed by investors. “People bought at the capped rate and sold at the market rate. Without a lock-in period of 10-15 years, these affordable homes don’t stay affordable.” He believes the government needs to subsidise land, cap sale prices, offer margin flexibility, and institute resale lock-ins to prevent speculative buying. “Only then will developers truly see value in participating.”

Moreover, in many cities, EWS families have shown reluctance to take possession of completed AHP flats, often because these are located in remote, underdeveloped areas with poor public transport and infrastructure facilities. CSEP’s study of Chennai showed that flats in city centres were quickly occupied, but those on the outskirts were vacant.

Says Ashwinder R. Singh, vice chairman of BCD Group and chair of the CII Real Estate Committee: “In India’s big cities, the AHP model makes sense in principle. But without addressing the ground-level challenges, delays, and affordability, it won’t scale. If we want developers to participate meaningfully, the government needs to do more than just subsidise; it needs to simplify.”

As of now, the AHP scheme remains underutilised. The disparity is evident in physical progress: while 5.23 million BLC homes have been completed, only 1.22 million AHP/ISS homes are finished, with over 487,000 units still under construction as on June 2, 2025.

CLSS: Many low- and middle-income Indian families rely on a loan to buy home. Recognising this, the Centre in 2015 rolled out the CLSS, one of its more popular sub-schemes under PMAY-Urban to reduce the cost of borrowing.

Once a beneficiary was approved under the scheme, the government would transfer a lump sum subsidy directly to their loan account. This brought down the outstanding principal, thus reducing the EMIs.

Families from different income brackets, EWS, LIG, and mid-income groups (MIG-I and MIG-II), could avail of an upfront interest subsidy on home loans. For EWS (income up to Rs 3 lakh), the scheme offered a 6.5 per cent annual interest subsidy on loans up to Rs 6 lakh for homes sized up to 45 sq.m; for LIG (Rs 3-6 lakh), the same subsidy rate is applicable, but for slightly larger homes (up to 60 sq.m); MIG-I (Rs 6-12 lakh) and MIG-II (Rs 12-18 lakh) received lower interest subsidies, 4 per cent and 3 per cent for homes sized up to 160 sq.m and 200 sq.m, respectively, on loans up to Rs 9 lakh and Rs 12 lakh.

Across categories, the maximum loan tenure was 20 years, and the net present value (NPV) rate was 9 per cent. This translated to a subsidy payout of up to Rs 2.67 lakh for EWS households, reducing monthly EMIs by roughly Rs 2,500. MIG beneficiaries would have savings between Rs 2,200 and Rs 2,250 a month.

With over 2.5 million beneficiaries, CLSS became the second-largest vertical under PMAY-U, after BLC. The scheme was officially wound up once the target was met, and all sanctioned subsidies were disbursed.

But there were problems with this route, too. The CSEP study found many design flaws in this scheme. One major issue was timing and uncertainty. At the time of loan application and home purchase, borrowers had no clarity on whether their CLSS application would be approved. Financial institutions, too, could not reliably factor the subsidy into the loan amount. So, instead of helping buyers stretch for a better home, CLSS often did little more than marginally ease the EMI on a house they could already afford.

The delays didn’t help either. If the Central Nodal Agency (CNA) took time to approve or release the subsidy, borrowers would be left servicing larger EMIs than they had planned for. This made banks wary of approving higher-value loans in anticipation of subsidies that might not come through on time.

Another issue was targeting. Only about 21 per cent of CLSS beneficiaries came from the EWS category. Factors, such as lack of documentation, informal employment, and credit invisibility kept these families outside the formal lending system, and by extension, outside the CLSS net. However, it did cater to 55 per cent of LIG and 24 per cent of MIG households.

Silver Lining Ahead For PMAY?

In the wake of soaring prices of units by private developers and only part-success of the government schemes, what are the options for buyers.

Those who qualify for PMAY have a ray of hope. PMAY-Urban 2.0, which was launched in late 2024, represents the government’s renewed attempt to course-correct and extend housing support to a wider spectrum of urban families. It sets a new target: 10 million additional homes by 2029, with a budget of Rs 2.3 lakh crore.

The new framework builds on the earlier scheme’s architecture, but introduces critical tweaks. Among its four verticals, BLC, AHP, ARH, and the new ISS, the last one addresses the lessons learnt from CLSS.

The intent is clear: to cushion borrowers from rising EMIs and encourage them to take the leap into ownership. The subsidy is paid in five annual instalments directly into the borrower’s loan account, thus easing the financial pressure year after year. Unlike CLSS, which operated more like a post-loan rebate, ISS is structured to give both the borrower and the lender clarity at the very beginning.

However, it comes with certain conditions. Under this scheme, beneficiaries can avail up to Rs 1.80 lakh in interest subsidy on loans up to Rs 25 lakh, provided the total value of the house doesn’t exceed Rs 35 lakh. The home has to be the buyer’s first property, and there are income ceilings and area limits that must be met. For instance, EWS households (earning up to Rs 3 lakh a year) and LIG households (Rs 3-6 lakh) are eligible, provided the carpet area doesn’t exceed 120 sq.m.

It’s also important to clearly distinguish the PMAY initiatives from the broader real estate trends. PMAY, while ambitious, is designed to ensure basic shelter to those who otherwise might never afford one, and comes with eligibility criteria and defined cost limits. Their pricing structure, typically capped around Rs 35-45 lakh, exists in a landscape where private developers define affordable homes as those starting from around Rs 50 lakh to Rs 1 crore, depending on the location and size.

What’s The Way Forward?

India’s housing market is not building enough homes that mid- and low-income families can afford. The minimal supply that does exist is either delayed, unoccupied, or increasingly pushed out to areas that are logistically and economically unfeasible for most buyers.

This reality calls into question the relevance of existing affordability thresholds. Should the Rs 45 lakh cap be redefined? Should carpet area caps evolve with urban density? Most importantly, can a blanket definition of affordability be applied to metro cities, such as Hyderabad and Mumbai, and tier-II towns and fringe areas near Delhi NCR?

Singh says: “You can’t have one national price tag for affordable housing when city markets are so different. The cap of Rs 45 lakh might work in some smaller cities, but in places, such as Mumbai, Bengaluru or Delhi NCR, it’s unrealistic. The cap has to be city-wise or zone-wise, reflecting land prices and income levels. Otherwise, you are excluding most urban buyers from the so-called affordable bracket.”

India’s housing market is not building enough homes that the mid- and low- income families can afford. The minimal supply that does exist is unfeasible for most buyers

The market redefines affordable homes with every passing quarter. Says Hiranandani, “The Government of India’s definition of affordable housing under PMAY does not align with actual construction costs in metro cities, where a Rs 1 crore cap would provide the much-needed cushion for developers to sustain such projects. As an industry body representative, we strongly recommend revising this definition to reflect market realities.”

According to Jasuja, redefining affordability is not just a matter of pricing, but one of land access, project scale, and economic feasibility. “Without deeper government support, especially through subsidised land, capped sale prices, and a buyer lock-in mechanism to prevent speculation, the dream of accessible urban homeownership may remain just that.”

Adds Hiranandani, “Fiscal incentives, such as subsidies, reduced stamp duties, and lower land costs would significantly enhance project viability. Streamlining approval processes and encouraging the adoption of innovative construction technologies, such as Mivan, which uses pre-engineered structures and prefab, are recommended to reduce costs and improve efficiency. Tax rationalisation and reinstating input tax credit for affordable housing would play a crucial role in making this segment viable while ensuring it meets the increasing demand for housing within the urban centres.”

As the data lays bare and the experts affirm, the affordable housing market is not simply facing a seasonal slump. It’s the result of deeper economic and policy contradictions.

“The demand is permanent,” says Singh, “but the problem is supply economics. Costs have gone up across land, materials, labour, and compliance—so developers find it tough to make viable projects in this segment. It is not broken, but unless cost structures and approvals ease, supply will keep falling short. This is not just a cycle, it’s a structural issue that needs correction.”

But some possible answers lie in the long term, particularly in how infrastructure planning can complement affordable housing development. Jasuja believes strategic public infrastructure is one of the few scalable solutions to recalibrate affordability.

Says Jasuja: “By creating the Atal Setu in Mumbai or the new airport in North Bangalore, where the government owns land, they can offer affordable housing nearby. With connectivity, these now-cheap areas become viable for homebuyers. The key is pairing infrastructure creation with timely supply.”

Meanwhile, the rate cuts by the RBI could be a crucial trigger for sentiment recovery in the residential housing market.

“With interest rates now likely to fall closer to 7.50 per cent (from around 8.25 per cent), EMIs on a Rs 1 crore loan could drop to somewhere between Rs 68,000-70,000 per month,” says Ankit Shah of Grahm Realty, a real estate advisory firm. This could be a significant dip for households already juggling inflation and other costs.

For mid-income and low-income buyers, the primary target group for affordable housing, this could be the breathing space they actually need. There is optimism that buyers sitting on the fence, particularly in the low-income and mid-income segments, may re-enter the market if pricing normalises in the second half of the year, according to Anarock’s Q1 2025 report.

Affordable housing was once pitched as an economic stimulus and a moral imperative, and seen as an engine of inclusive urbanisation. But today, it survives more on bureaucratic architecture than private conviction. For it to truly succeed, India needs more than just schemes; it needs structural solutions that are in sync with the real estate market. Until then, the gap between affordability and access will only continue to grow.

anuradha.mishra@outlookindia.com