Two years ago, when Shashi Kant Sharma, now 76, returned to his job of a security guard in Surat after spending a few months with his family in Delhi because of a serious illness, he was in for a shock. The company he had worked for since 2007 had shut down without notice. Unable to find another job, he returned to Delhi, and faced another shock—his brothers refused to keep him on a permanent basis and he had already given his house to his wife, with whom he had long-standing differences.

As his meagre savings ran out quickly on lodging and fooding, Shashi took refuge at Rain Basera, a government-run night shelter for the homeless. From there, he was picked up by Saint Hardyal Educational and Orphans’ Welfare Society (SHEOWS), a non-governmental organisation (NGO), which runs old- age homes across India, in Delhi in 2024, where he now lives. “The family has nothing to do with me since I have been at the old-age home, but they know where I am,” he says.

Shashi is not a lone case. According to the HelpAge study released in June 2025, Understanding Intergenerational Dynamics & Perceptions, approximately 34 per cent of the seniors feel neglected and are abused in old age. Financial and physical vulnerability leaves many helpless, often preventing them from reporting neglect or abuse to authorities, either due to lack of information, reluctance to confront the family or the fear of social stigma.

Says Dr G.P. Bhagat, founder, SHEOWS: “When medical issues, such as dementia arise, family members start avoiding seniors rather than taking better care of them. Further, after a spouse’s death, the surviving spouse becomes vulnerable to neglect, and is often abandoned by the family.”

Most seniors are, however, unaware that they can go for legal remedy. Shashi expected his family to take care of him, but has no idea about what he is entitled to. We have put together a list of rights seniors should be aware of to lead a better life.

Rights of Seniors

The Maintenance and Welfare of Parents and Senior Citizens (MWPSC) Act, 2007, is an overarching law that seeks to protect seniors from abuse and help them live a life with dignity. The Act provides for the maintenance of parents and seniors, protection of life and property, medical care, and defines offences and procedures for trial. Article 21 of the Constitution of India guarantees protection of life and personal liberty, including the right to live with dignity, while Article 41 ensures the right to work, education, and public assistance in old age, sickness, and disability.

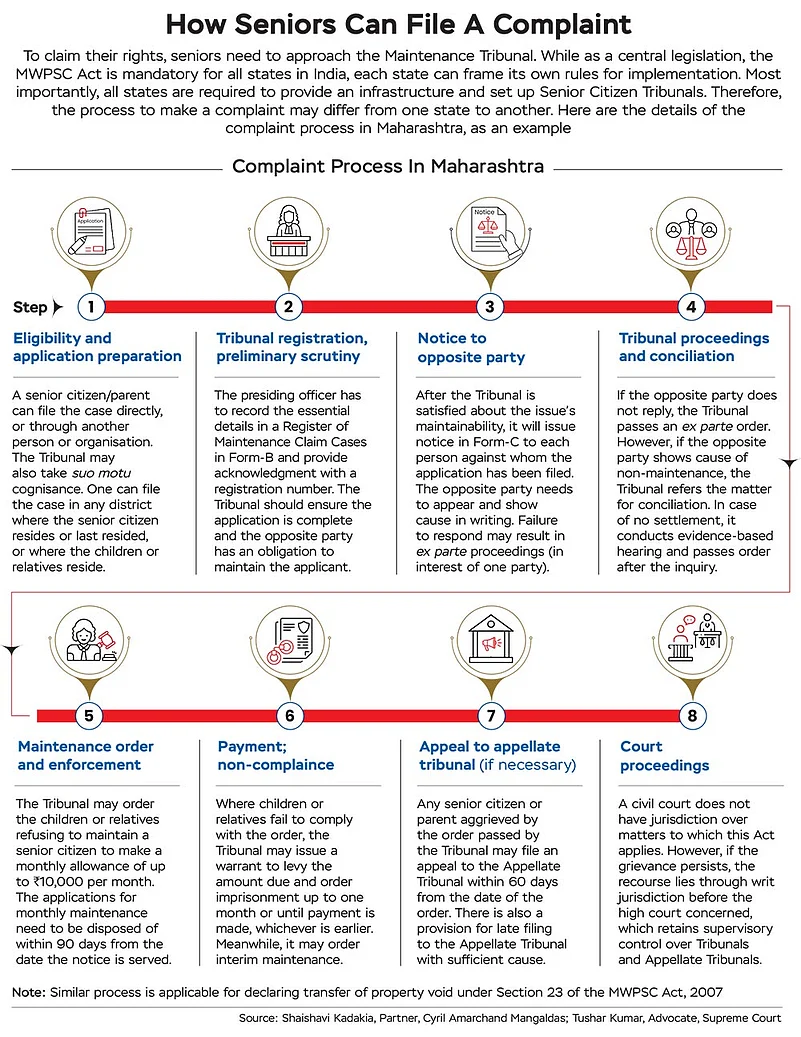

According to Shaishavi Kadakia, partner at law firm Cyril Amarchand Mangaldas, the Act provides four key rights.

Right To Maintenance: Senior citizens who are unable to maintain themselves are entitled to make an application for maintenance against one or more of their children (not a minor) or a relative (in case of a childless couple) who is the legal heir (not a minor) and is in possession of or would inherit their property.

Tushar Kumar, a Supreme Court advocate, explains: “The Act provides for maintenance covering food, clothing, residence, medical treatment, and attendant care.”

Property Protection: A gift or transfer of property can be declared void at the option of the senior citizen if the gift or transfer of property is deemed to have been made by fraud, coercion, or undue influence.

“The Act also empowers Tribunals to grant interim relief, to order time-bound decisions and to declare void the transfers of property where such transfers were conditioned upon care, but were followed by neglect or abandonment,” says Kumar.

To ensure property rights, courts, have in several judgments, ordered maintenance and even allowed revocation of gift deeds, where parents signed to transfer property to their children. In Vijay Tejrao Ugale vs Kesarabai Tejrao Ugale (June 2025) case, the Nagpur Bench of Bombay High Court upheld a tribunal decision ordering a monthly maintenance of Rs 10,000 from the son to his 77-year-old mother. Similarly, in S Mala v. District Arbitrator (March 2025) case, the Madras High Court ruled in favour of an elderly mother, allowing revocation of the gift deed transferring her property to her son, when the son neglected her.

The Tribunals are also empowered to declare gift deeds null and void if the implied condition of maintaining the elderly parents is violated.

Medical Care: State governments have to ensure a sufficient number of government hospitals and geriatric care facilities in every district.

Old-Age Homes: State governments may set up old-age homes, one in each district, for minimum 150 senior citizens. Kumar adds, “The statute compels state governments to set up old-age homes in every district, allocate beds for geriatric treatment, and protect life and property through district magistrates.”

The Obstacles

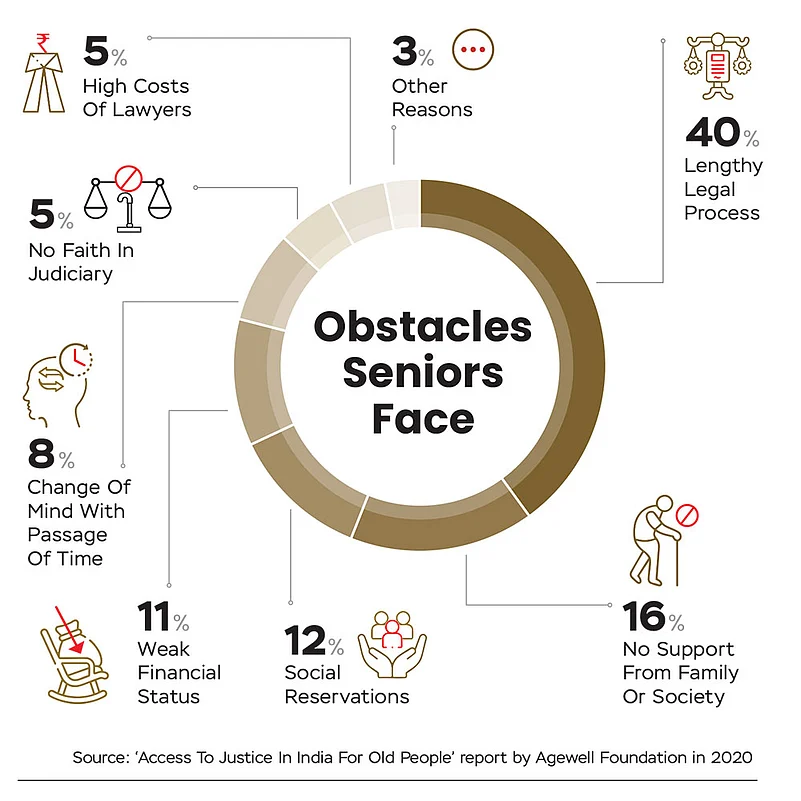

There are several obstacles that come in the way when it comes to seniors seeking legal help or remedy (see Obstacles Seniors Consider).

Lack Of Awareness: The HelpAge India report cited earlier shows legal awareness among the elderly is significantly low. For instance, about 68 per cent know about government pension schemes, but only 35 per cent understand legal rights and remedies.

Emotional Demons: Going against the family or asking for maintenance from children or fighting for the property does not seem right to many elderly people. Says Bhagat, “Even if they know the law, they don’t pursue it because of physical frailty or conditions like dementia.”

Many elderly refrain from taking legal recourse, either due to lack of awareness of the law or because of the emotional tussle of fighting a legal battle against children

The deeper problem lies in societal norms. It is often emotionally taxing for elderly parents or senior citizens to take legal action against children they have cared for their entire lives.

Lengthy Legal Process: A 2020 report, Access To Justice In India For Old People by Agewell Foundation, a not-for-profit organisation, found that 40 per cent of the elderly avoid the legal route due to the lengthy procedure. Other deterrents include lack of family support, social stigma, change of mind with time, distrust in the judiciary, and high litigation cost.

Financial Constraints: Financial standing also poses a hindrance, as litigation costs money. Says Kumar: “The expenses typically borne by senior citizens are related to documentation, attestation, or incidental costs of service of notice. Should the matter reach a high court, the court fees are nominal, ranging from a few tens to a few hundred rupees, but a significant outlay arises from advocate fees, which can vary.”

Are Tribunals Effective?

The procedures and rules are senior-friendly largely, but timing is still an issue in some cases.

The dispute resolution mechanism, including conciliation, is a speedy and non-expensive mechanism in which the conciliation officer submits the findings on the dispute within one month to the Tribunal, and if an amicable settlement is arrived at between the parties, then the Tribunal passes an order, says Ruchita Datta, Partner, D&T JURIS.

She adds: “Tribunals adopt summary procedures so that the cases are disposed of within a reasonable time and without much hassle to the senior citizens/parents.”

What helps is that Tribunals have enough teeth to grant interim maintenance, to order eviction of abusive heirs from the property of senior citizens, and to enforce orders by way of warrant or imprisonment, says Kumar.

“But, the effectiveness varies across jurisdictions, depending on awareness, infrastructure, and judicial oversight,” he adds.

In India, legal recourse is usually the last resort due to the protracted and paper-heavy process. For seniors, legal battle with family, especially children, also becomes an emotional issue. However, knowledge of legal rights, procedures, and timelines can empower seniors to protect themselves against financial, psychological, or physical abuse and ensure a dignified life in old age.

versha@outlookindia.com

Senior citizens may call on the elderline #14567, for health and shelter related information, legal guidance, and emotional support